Yup. I’m going there. And nope, this post has nothing to do with autism. Also, this post is definitely going to be a bummer. Here we go…

When my mother suggested that I write an essay titled “Watching My Mother Kick the Bucket”, I confessed to her that the idea–if not the title–had already occurred to me. Somewhere along the way, writing has become a way of processing things for me, but also for memorializing them. And apparently I have my mother’s blessing for this act of public hand wringing.

Fact: my mother has been battling lymphoma in one form or another since I was approximately two months old. And although she is about to die from it, this fact, at 80 years of age, actually makes her a survivor.

I was blissfully unaware of the first round of this match, and did not have to experience it fully until I was pregnant with my son at 27. I remember her telling me that her cancer had returned, as I was on my way to meet a group of other soon-to-be moms for a walk around the National Mall. Within weeks, my parents had returned to the U.S. after living in Venezuela for two years. I helped my parents unpack, and laid in bed with my mother, her sick from chemo, and me trying out new boy names in my head. Later that year, we snapped photos of our son as a hairless newborn, dressed as Santa and held by my Mom, who was also wearing a Santa cap to cover her own bald head.

There have been several battles (they’re more like attacks, I think) since then, including a moment in 2018 when my brothers and I traveled with our mother to Sweden for a farewell to her country of birth. It was a magical trip, which my cynical family looks back on with nostalgia and gratitude. We met old and new relatives, were treated to moose meatballs and endless ficka, and walks through troll forests and 600 year old fishing villages. As we walked through familiar sites in Sundsvall, each of us, including my mother, recalled memories of our time there as children. I guess I have cancer to thank for those good memories, now that I think about it.

But folks, we have reached the end.

I have chosen to use the word dying a lot lately in conversation. My husband hasn’t been happy with that word choice. But for me, it is therapeutic. It is preparatory. It is, in fact, how the New York Times describes the people it features in its obituaries–there’s no “passed on”, “no longer with us”, “gone to a better place”, or even “deceased”. Fuck euphemism. Let’s call it what it is. Let us speak of what is really happening to the person I have known longer than anyone else in my life.

Multiple, Uncomfortable Facts: In the past week, I have chosen the box that my mother’s ashes will go into, and settled on a profanity-laced inscription, with her blessing. I have also washed a pillow four times in a row to get her blood out of it (mostly). I have helped her change into her pajamas every night, just like she did to me when I was a baby. I have walked quickly out of the room to give her privacy while she vomited. I shared a surreal moment with my mother, brother, father, and sister-in-law where five people debated the best way to draw out blue liquid morphine from a bottle so that she could have easy access to it, should the unbearable pain hit her in the middle of the night. My Dad has become an amateur wound care specialist. I have witnessed multiple octogenarians openly discussing my mother’s impending death while nibbling on the Swedish cinnamon rolls I baked for my mother’s goodbye coffee klatches. I have sat with complete strangers (hospice workers) and listened to them explain to her that hallucinations are possible and normal, and that morphine can arrive on your doorstep via a same-day delivery service. I asked a different stranger to explain to me exactly what will happen to her body, when she dies at home, down to the type of van that will arrive within 90 minutes after that terrible phone call is placed. There is a very orange DO NOT RESUSCITATE sign next to my parents’ fridge, where I get my half and half in the morning.

New Discovery: We are apparently efficient writers of obituaries in my family. Within two hours, we had written–between five of us–a short, witty version of my mother’s life, and given it to her to edit and sign off on by that evening. Consistent to the end, my family does not beat around the bush. This morning, after breakfast, we settled on a loose plan for a memorial service shortly before my brother said his goodbye and headed back north.

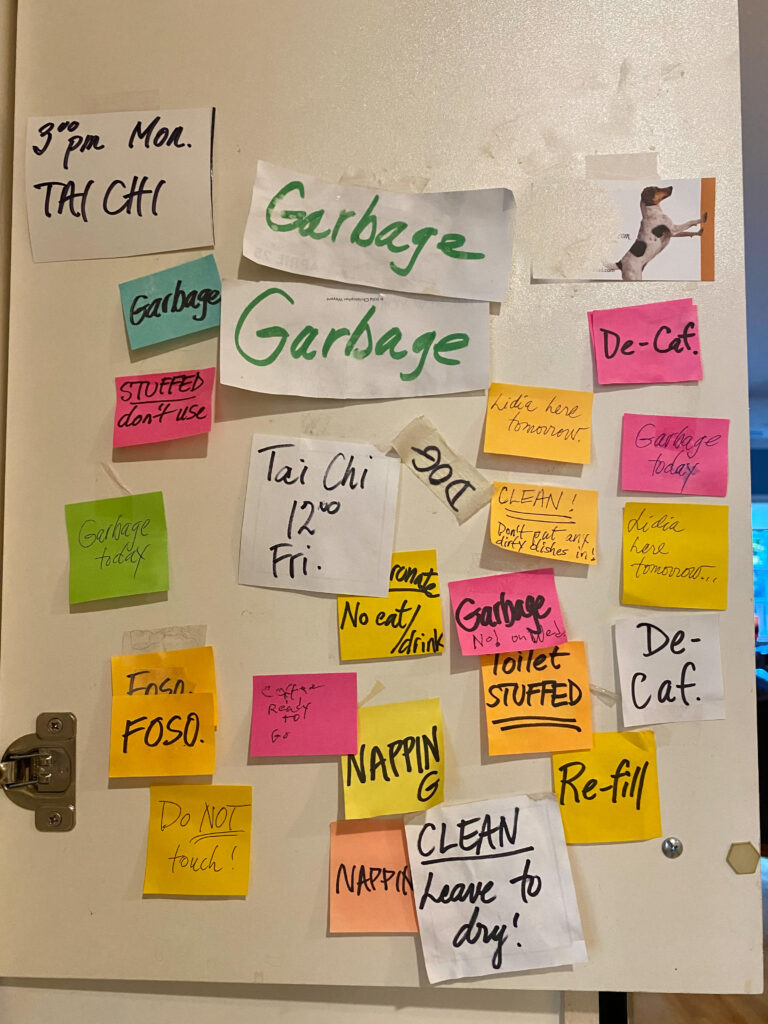

New Habits: I have started changing verb tenses in my head already, practicing. When I hear her say “I go”, “I like to”, or when my dad tells me how my mom likes him to do things around the house, I’m already internally practicing the past tense version of these phrases. I’ve also noticed her maddeningly thorough penchant for labeling everything in her house and wondered if she knew that her labels would outlast her, that she would continue to help her family figure out which Tupperware bottom belongs with which top, long after she is turned into ashes.

I guess the main theme here is this: why fuck around? My mother is dying. Let’s call it what it is. As my mother declared yesterday, after I finally relented and took her and my grandmother’s wedding rings from her fingers, “let’s not play games”.

I have begun to wonder why we don’t we talk about these things beyond the confines of the rooms in which we care for the soon-to-be dead. I am certainly not the only person in my Facebook feed who has helped their parents through hospice. Shit, let’s dispense with the “being in hospice” part. Let’s call it “dying“. And for those of us who stay with our loved ones through these painful last days, let’s call that what it actually is: we are helping our loved ones die.

We are staring at calendars and calling our kids several states away on the phone and wondering whether our parents will be done dying by a certain date, or whether we should bother washing our mother’s bloody sweater, since she’s got more sweaters on the shelf than she probably has days left living. We do the laundry, stack the dishes, and put the daily objects of our loved ones’ lives back in the closet, wondering what the point of all of this ritual is when the end is so near. What the hell am I supposed to do with her unfinished knitting project?

Back to my point: why can’t we talk about this stuff publicly? Why can’t I say that my mother is “dying”? Why don’t we all admit how awkward and awful it is to go through the everyday activities of living during the final weeks of life–when it feels utterly pointless to talk about Russian’s impending invasion of Ukraine at the dinner table, when what actually feels better is to perform a group edit of her slightly snarky obituary?

Collectively speaking, our lives have become an Instagram performance piece. Our public confessions barely scratch the surface, and serve only to collect “likes” and “thanks for keeping it real” comments. Our deaths are now memorialized Facebook pages and generic obituaries on funeral home websites.

With my mother’s blessing, I am describing what it is like to watch her “kick the bucket”. Our story–while singularly awful to my family–is not unique. We share all of the other private moments of our lives so readily these days. Why can’t we speak openly of death?